•the national pastime

Text written by Albert Kilchesty

Pittsfield Baseball 1791 Brand

In 2004, baseball historian John Thorn discovered a document that revealed startling new evidence about the origins of the game. The document indicates that the town elders of Pittsfield, Massachusetts had become fed up by the number of complaints about windows broken by errant baseballs. Therefore, anyone found guilty of this “misdemeanor” would be fined five shillings. Broken windows have put a premature end to many sandlot games, for sure, but what made this edict of special interest to historians was its date of issue—1791! That’s a half-century earlier than the date given to the fabricated Doubleday origin myth. And it also provided proof of the game’s origins in the English games of rounders and cricket. Massachusetts colony, as we know, was founded by English Puritans fleeing from religious persecution in their home country. Some form of baseball had been played in Plymouth—site of the Mayflower’s crash landing—where it was later proscribed by Puritan party poopers. Pittsfield can now lay claim as the birthplace of baseball, at least until the next discovery proves otherwise.

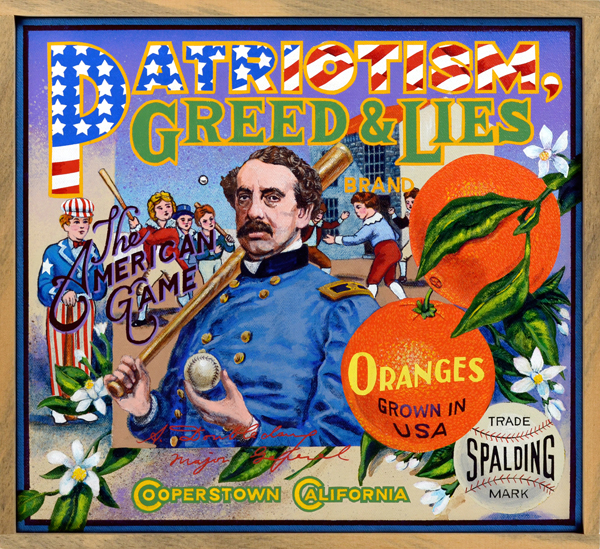

Patriotism, Greed & Lies Brand (Baseball Reliquary collection)

Just for the record, Abner Doubleday did not invent the game of baseball one fine day in Cooperstown, NY. Baseball’s great creation myth has no basis in reality: its antecedents were such games as cricket and rounders, imports from the British Isles. Over time these games were modified, their rules codified, to fit the American character. The only thing that grew in baseball’s Garden of Eden was garden-variety capitalism. During an era marked by American imperialist expansion, it was deemed important that the latest American export—baseball—could “prove” emphatically that it originated here. Enter Albert Goodwill Spalding (1849‒1915), pitcher turned entrepreneur, who sat atop a growing business empire that included the manufacturing and sale of baseball equipment and publications, notably the annual Spalding Guide to Base-Ball. In 1908 he convened a group of baseball executives, known as the Mills Commission, to root out the origins of our national pastime. When someone discovered a beat-up baseball dating from 1839 in the attic of a Cooperstown resident, the deal was cinched. Baseball was incontrovertibly of American origin, ‘nuf said. The Doubleday Myth was born, the flag waved, and cheers echoed throughout the land. Decades would pass before the myth would be proven a confabulation.

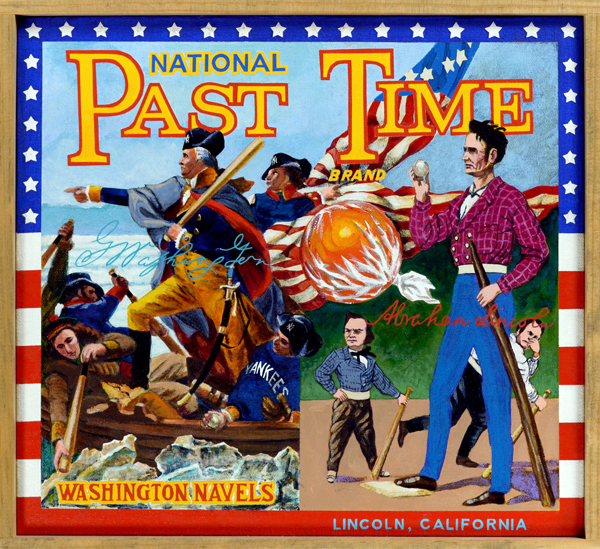

National Past Time Brand (private collection)

Contemporary research claims that baseball, or some form of stick-and-ball game, was played by soldiers under George Washington’s command during the Revolutionary War. It’s a tantalizing thought, that these Yankees (see the figure in the boat) played ur-baseball during the 1770s. Long, tall Abraham Lincoln was also said to have once played the game, although it’s uncertain how well the ol’ rail-splitter wielded the ash. To the left of Honest Abe is his successor, Andrew Johnson, pictured here as a midget on-deck batter, a fitting interpretation of this man of small gifts.

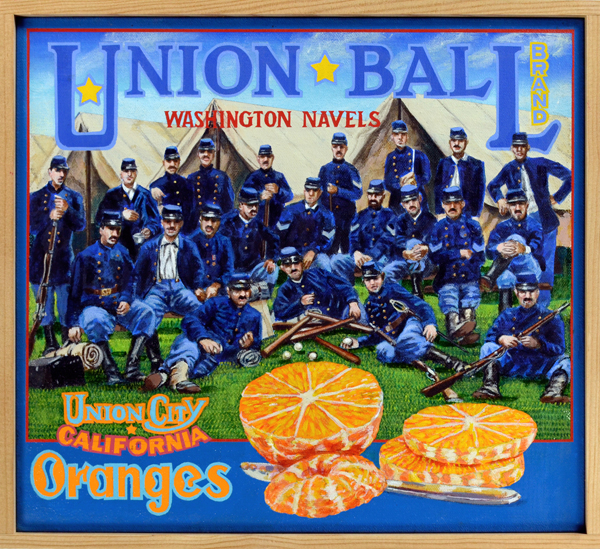

Union Ball Brand

Baseball soared in popularity during the nineteenth century as Union soldiers from the cities of the north spread its gospel during the Civil War. Contrary to popular belief, baseball is an urban game, not a pastoral creation played out against the background of a mythical Eden. Although some form of ball and bat games were popular everywhere, many rebel soldiers from the agrarian South hadn’t known the “New York Game”—played on a diamond, with codified rules—until Union prisoners of war introduced it to them. These games between soldiers filled in their leisure time and gave them a much-needed respite from the horrors of war. After the conflict, soldiers returned home and spread the game throughout the South and the West. By the 1870s, baseball had taken root everywhere, giving birth to our national pastime.

Remember the Maine Brand

This U.S.S. Maine baseball team won the Navy baseball championship in late 1897. They beat a nine from the U.S.S. Marblehead 18‒3 in a game played at Key West, Florida. The team’s ace pitcher was William Lambert, an African American, seen in the back row. On February 18, 1898, less than two months after the game, the Maine exploded and sank in Havana harbor, lighting the fuse for the Spanish-American War. The disaster claimed the lives of 260 crew, including all of the players except for John Bloomer, in the back row at far left, underneath the word survivor. Although later investigation revealed that the ship sank as a result of an explosion in its armory, and not as a result of enemy attack, the jingoistic call “Remember the Maine!” successfully obscured the truth from the public at the time.