•steroids

Text written by Albert Kilchesty

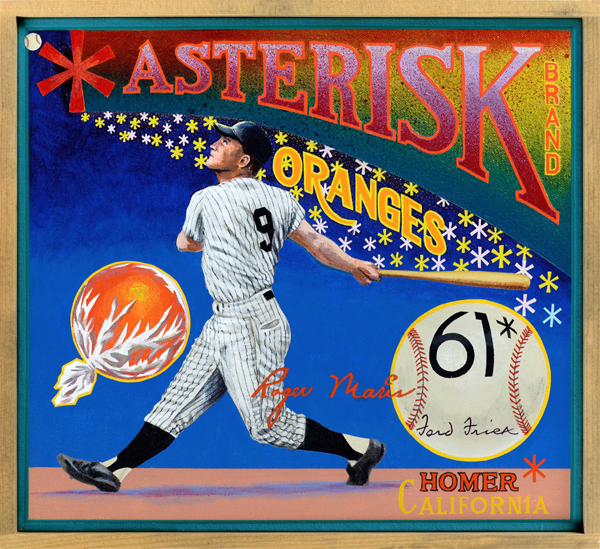

Asterisk Brand (Baseball Reliquary collection)

In a game ruled by numbers, few possess the magic of “60”—the number of home runs hit by Babe Ruth in 1927.n a game ruled by numbers, few possess the magic of “60”—the number of home runs hit by Babe Ruth in 1927. It was once thought that no player would ever exceed that number of homers in a season. And if anyone did, then naturally it be a superstar, a player like Mickey Mantle, for example, not a mere mortal. When the American League expanded to ten teams in 1961, adding eight more games to the schedule, Mantle indeed looked like the odds-on favorite to surpass the Babe. But after an injury sidelined him for the season, the pursuit of the record was taken up by his teammate, Roger Maris. Maris (1934‒1985) was a reserved, hard-working player of very good ability, an All-Star and former MVP who suffered only because he wasn’t good copy, unlike the dynamic Ruth or Mantle. When it became clear that Maris would break the home run record, Ford Frick, the Commissioner of Baseball who had once served as a ghostwriter for Ruth, declared that an asterisk would be placed by the name of the player who hit 61 or more homers. The asterisk would indicate that the record was established over the new 162-game schedule, not the previous 154-game slate. That damned little star followed Maris to an early grave.

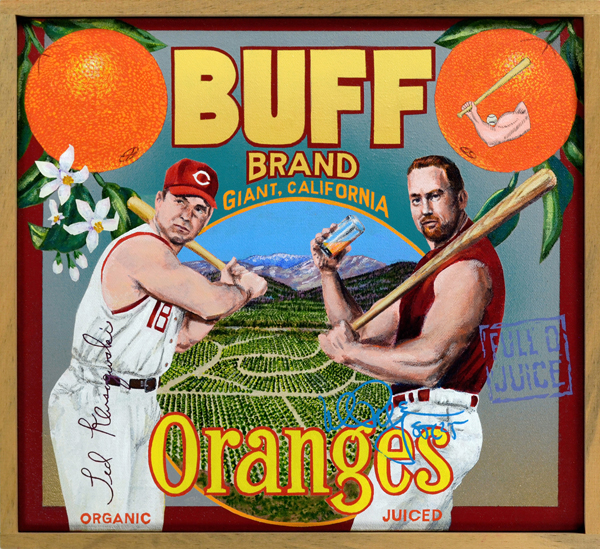

Buff Brand

The finely sculpted, artificially enhanced beefcake on display during the Steroid Era made former baseball strongmen like Ted Kluszewski (left) look sadly deficient, almost anorexic, by comparison. “Big Klu” came by his nickname naturally. The 6’ 2” first baseman for the Cincinnati Reds during the 1950s had biceps so bulky that they couldn’t be contained by his uniform. Klu had his best season in 1954, slugging 49 homers and driving in 141 runs, both National League-leading marks. His signature, bare-armed look is burned into the memories of a generation of fans—his baseball cards prized, his name a metaphor for a more innocent era. Mark McGwire (right) is the poster boy for an era as well, one associated with artificiality and excess. In the court of public opinion he and his pumped-up cronies are guilty of perpetrating the greatest con in American sports history. Whose legacy would you choose?

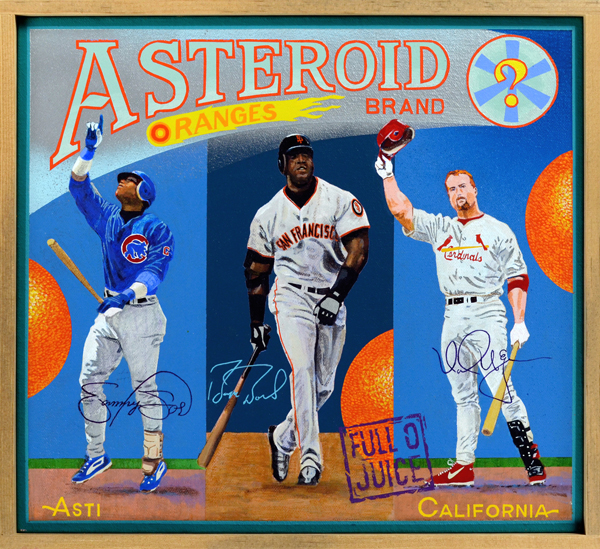

Asteroid Brand (Baseball Reliquary collection)

The Great Home Run Race of 1998 between Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa was, depending on one’s point of view, either the most marvelous or most grotesque display of slugging in history. Day by day fans watched as these two good-naturedly battled to pass the single-season record of 61 home runs set by Roger Maris. At season’s end, both would leave the previous record in tatters—Sosa finished with 66 circuit clouts, McGwire with an unimaginable 70 long balls. During the season, a sharp-eyed reporter noticed a bottle of androstenedione, a supplement used to build muscle mass, in McGwire’s locker. Although legal at the time, the revelation caused some to question whether something more powerful, like steroids, was also being used. By the time Barry Bonds (center) used his Michelin Man physique to powder 73 long balls in 2001, there remained few who didn’t doubt that players were bulking up through illegal means. Ensuing revelations of steroid abuse rocked the baseball world, forcing many to question the validity of these records.

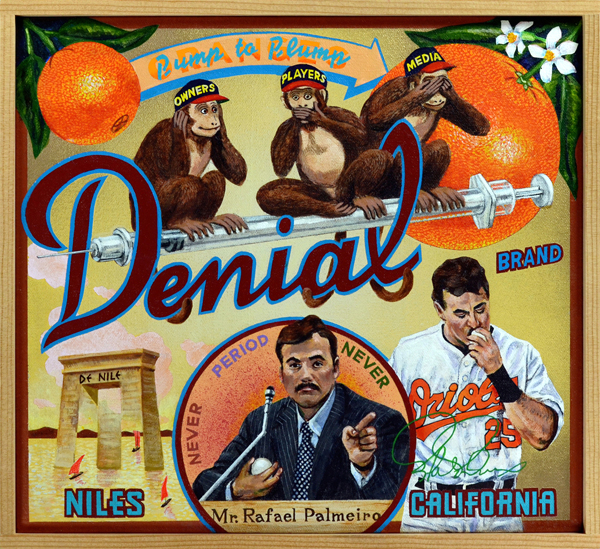

Denial Brand

The most powerful images often carry more weight than the contents of a law library. The four small images that make up this series, and this painting in particular, present the complexities of The Steroid Era more succinctly than tens of thousands of words have yet accomplished. Former Orioles first baseman and designated hitter Rafael Palmeiro was one of several players called upon to provide testimony during congressional hearings designed to root out the truth behind allegations of steroid abuse in Major League Baseball. He, and others, flatly denied ever using any form of artificial, performance-enhancing drugs despite evidence to the contrary. In fact, the entire network of owners, players and the press colluded to minimize the role these substances played in baseball during the 1990s and 2000s. There was simply too much money at stake to allow ethical considerations to interfere. After the strike that cancelled the 1994 World Series, baseball responded in the way it always had when fan disaffection threatened profits—it pumped up offense. Besides, as an ad campaign from the time declared, “Chicks dig the long ball,” the more the merrier. Home runs and profits increased astronomically, but so did suspicions that something was rotten in Mudville. It was.