•poetry in motion

Text written by Albert Kilchesty

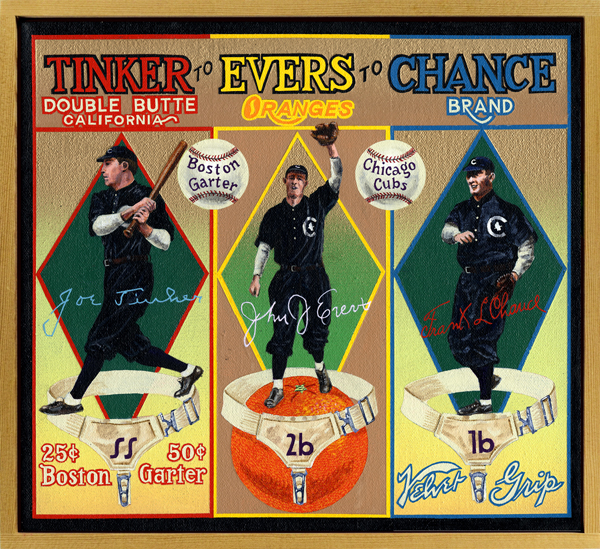

Tinkers to Evers to Chance Brand (private collection)

“These are the saddest of possible words / ‘Tinker to Evers to Chance’ / Trio of Bear Cubs and / fleeter than birds / Tinker to Evers to Chance.” So begins baseball’s most famous piece of doggerel, written by journalist Franklin P. Adams in 1910 as filler for his weekly column in the New York Evening Mail. Shortstop Joe Tinker, second baseman Johnny Evers and first sacker Frank Chance, three-quarters of the Chicago Cubs starting infield, did indeed make life dismal for their archrivals, the detested New York Giants. The trio wasn’t all that skilled in turning double plays, but it seemed always to make them at crucial times versus the Giants. “Tinker to Evers to Chance” has entered the vernacular as a phrase synonymous with skill and precision, a group working together successfully like a well-oiled machine. What many didn’t know was that for years Evers and Tinker hardly spoke to one another after having had a nasty argument. No one can argue with their success, however—the three played on NL pennant winners in 1906 and 1910, and led the Cubs to the 1908 World Championship, the last Cubs team to accomplish that feat. They were inducted into the Hall of Fame together in 1946, more for their place in baseball culture than for their play on the field. Boston Garters was a company that made—what else?—garters; in 1912 it issued a baseball card set that many collectors believe is among the most beautiful ever produced. Oh, and if you were wondering, a gonfalon is simply an esoteric substitute for the word pennant.

BASEBALL’S SAD LEXICON

These are the saddest of possible words:

“Tinker to Evers to Chance.”

Trio of bear cubs, and fleeter than birds,

Tinker and Evers and Chance.

Ruthlessly pricking our gonfalon bubble,

Making a Giant hit into a double—

Words that are heavy with nothing but trouble:

“Tinker to Evers to Chance.”

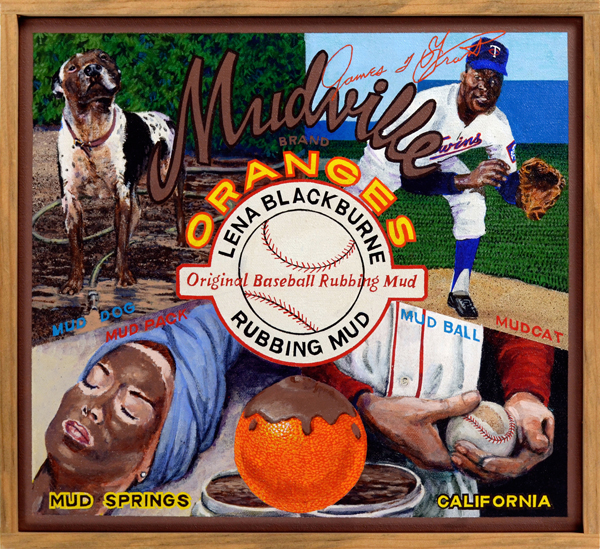

Mudville Brand

Baseballs fresh out the box have a slick, slippery sheen that makes it difficult for pitchers to grip and throw it with confidence. Prior to each game, an umpire rubs a few dozen balls with a combination of spit and a special mud designed to dull a ball’s gloss without perceptibly altering its appearance. The official mud of Organized Baseball was discovered by Lena Blackburne (1886‒1968), a former player, coach and scout, along the banks of Pennsauken creek in South New Jersey. The actual site is a secret, guarded closely by the Blackburne family, which still mines and markets Lena Blackburne Rubbing Mud. The mud has the consistency of fine silt, and is applied sparingly to each new ball: a 16-ounce container is normally enough for a whole season. Keeping with the theme of the painting, former Minnesota Twins pitcher Jim “Mudcat” Grant makes an appearance at top right.

CASEY AT THE BAT

The outlook wasn't brilliant for the Mudville nine that day;

The score stood four to two, with but one inning more to play,

And then when Cooney died at first, and Barrows did the same,

A pall-like silence fell upon the patrons of the game.

A straggling few got up to go in deep despair. The rest

Clung to that hope which springs eternal in the human breast;

They thought, "If only Casey could but get a whack at that —

We'd put up even money now, with Casey at the bat."

But Flynn preceded Casey, as did also Jimmy Blake,

And the former was a hoodoo, while the latter was a cake;

So upon that stricken multitude grim melancholy sat;

For there seemed but little chance of Casey getting to the bat.

But Flynn let drive a single, to the wonderment of all,

And Blake, the much despised, tore the cover off the ball;

And when the dust had lifted, and men saw what had occurred,

There was Jimmy safe at second and Flynn a-hugging third.

Then from five thousand throats and more there rose a lusty yell;

It rumbled through the valley, it rattled in the dell;

It pounded on the mountain and recoiled upon the flat,

For Casey, mighty Casey, was advancing to the bat.

There was ease in Casey's manner as he stepped into his place;

There was pride in Casey's bearing and a smile lit Casey's face.

And when, responding to the cheers, he lightly doffed his hat,

No stranger in the crowd could doubt 'twas Casey at the bat.

Ten thousand eyes were on him as he rubbed his hands with dirt.

Five thousand tongues applauded when he wiped them on his shirt.

Then while the writhing pitcher ground the ball into his hip,

Defiance flashed in Casey's eye, a sneer curled Casey's lip...

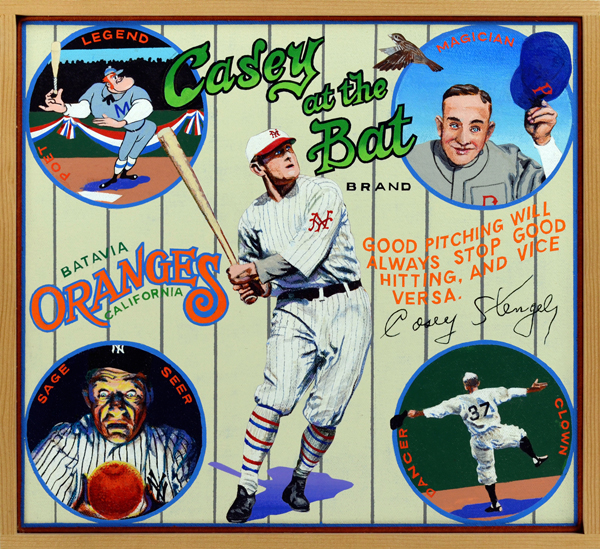

Casey at the Bat Brand (Baseball Reliquary collection)

Two legendary Caseys meet head-on in this painting: the mighty Mudville whiffer of poetry, and the brilliantly unorthodox tactician and noted creator of a private language, Casey Stengel. The first is the product of Ernest L. Thayer’s imagination, the eponymous slugger of the ballad Casey at the Bat, the tale of a man undone by hubris. Thayer’s poem was published in 1888, attaining fame not in written form but in public performance. It is estimated that actor/orator DeWitt Hooper performed the work 10,000 times beginning in 1889, one year before the “real” Casey was born. As a player Stengel (1890‒1975) was perceived as a clown, a jokester, once giving a hostile crowd “the bird” by doffing his cap to reveal a real bird underneath. It was as manager of the feared Yankee dynasty, and later the maladroit Mets, that the legend of Casey was born. He skippered the Bronx Bombers to five consecutive World Series crowns in 1949 through 1953, winning ten pennants overall at the helm of the team. He was hired to manage the expansion Mets in 1962, and tried to divert journalists from the harsh realities of bumbling Mets baseball by spinning long, stream-of-consciousness yarns in fractured English called “Stengelese.” The late Jim Murray once remarked, “[Stengel has] a speech pattern that ranges somewhere between the sounds a porpoise makes underwater and an Abyssinian rug merchant.” His incessant mumbo-jumbo worked a special magic with fans, who dubbed him lovingly “The Old Perfessor.”

...And now the leather-covered sphere came hurtling through the air,

And Casey stood a-watching it in haughty grandeur there.

Close by the sturdy batsman the ball unheeded sped —

"That ain't my style," said Casey. "Strike one!" the umpire said.

From the benches, black with people, there went up a muffled roar,

Like the beating of the storm-waves on a stern and distant shore;

"Kill him! Kill the umpire!" shouted some one on the stand;

And it's likely they'd have killed him had not Casey raised his hand.

With a smile of Christian charity great Casey's visage shone;

He stilled the rising tumult; he bade the game go on;

He signaled to the pitcher, and once more the dun sphere flew;

But Casey still ignored it, and the umpire said "Strike two!"

"Fraud!" cried the maddened thousands, and echo answered "Fraud!"

But one scornful look from Casey and the audience was awed.

They saw his face grow stern and cold, they saw his muscles strain,

And they knew that Casey wouldn't let that ball go by again.

The sneer has fled from Casey's lip, the teeth are clenched in hate;

He pounds with cruel violence his bat upon the plate.

And now the pitcher holds the ball, and now he lets it go,

And now the air is shattered by the force of Casey's blow.

Oh, somewhere in this favored land the sun is shining bright,

The band is playing somewhere, and somewhere hearts are light,

And somewhere men are laughing, and little children shout;

But there is no joy in Mudville — mighty Casey has struck out.

Three Fingered Brown Brand

Mordecai Peter Centennial Brown (1876‒1948) anchored the Chicago Cubs pitching staff during the team’s great years at the beginning of the last century. He mangled two fingers on his right hand in a childhood accident. The injury forced “Three Fingered” Brown to adopt an unorthodox grip on the baseball, enabling him to throw an unusually wicked curve. The extraordinary movement of his pitches contributed to his success: he posted 20 or more wins in six consecutive seasons during his ten-year stint with the Cubs (1904‒1912). His mastery of the rival Giants and their superlative ace, Christy Mathewson, was complete. He bested Matty, the greatest pitcher of the era, nine consecutive times between 1905 and 1908. Brown won five World Series games, tossing three shutouts over nine appearances in four different series. He notched 239 wins during a fourteen-year career, and his lifetime 2.06 ERA is third best all-time. Brown is commonly known now as “Three Finger” rather than “Three Fingered.”

MORDECAI BROWN

by William James Lampton

Gloom gathers above us,

There's murk in the air,

There's no one to shove us

Along to get where

The crown of the victor

Will rest on this town,

For the Giants see nothing

But Mordecai Brown,

Mordecai, Mordecai

Three-fingered Brown.

Fans wail on the bleachers,

Fans weep in the stands,

Fans cry with the screechers,

For any way, every way,

Far up and down.

There's nothing that greets them

But Mordecai, Mordecai

Three-fingered Brown

Baseball is no longer

The game of a club

Which had it been stronger,

Might wallop the dub

That hails from the windy

And comes to this town

To razzle the Giants

With Mordecai Brown.

Mordecai, Mordecai,

Three-Fingered Brown.

The murky clouds thicken,

The end cometh on

When nothing can quicken

The hope that is gone;

Manhattan is busted,

The pennant is down,

And the Giants are walloped

By Mordecai Brown.

Mordecai, Mordecai,

Three-fingered Brown.

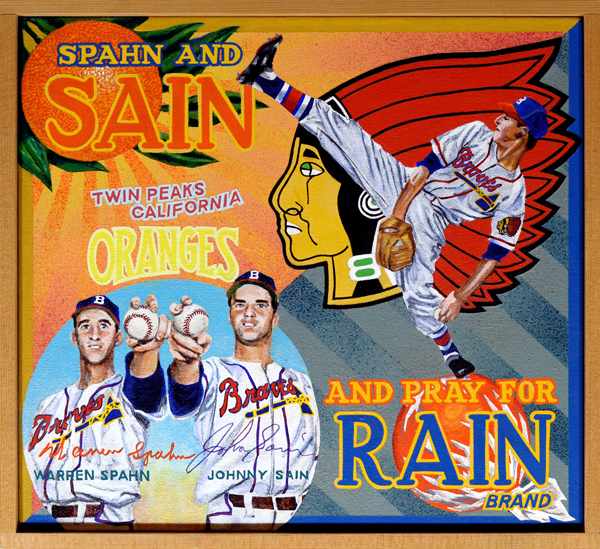

Spahn and Sain and Pray for Rain Brand (private collection)

During the final weeks of the 1948 National League pennant race, fans of the Boston Braves despaired over the perceived lack of pitching depth on their team. Locked in a tense battle with the Cardinals and resurgent Pirates, the Braves counted heavily on the performance of their top two pitchers, right-handed ace Johnny Sain, and his southpaw counterpart, Warren Spahn. The duo were the subject of a memorable bit of doggerel which appeared in the Boston Post on September 14th of that year. Penned by sports editor Gerald V. Hern, the simple poem’s opening lines were: “First we’ll use Spahn / then we’ll use Sain / Then an off day / followed by rain.” This was soon shortened to the “Spahn and Sain and pray for rain” lilt in use today. The Braves had other fine pitchers, Bill Voiselle and Vern Bickford, not included in the poem, one imagines, only because they had metrically unfriendly surnames. In any case Braves’ fans rallied around the cry, their pleas and exhortations answered as the team captured its first NL flag in thirty-four years. The Braves dropped the 1948 World Series in six to the Cleveland Indians, but the chant became a part of baseball lore, a fond reminder of the last National League Boston team to appear in the postseason.

SPAHN AND SAIN

First we'll use Spahn

then we'll use Sain

Then an off day

followed by rain

Back will come Spahn

followed by Sain

And followed

we hope

by two days of rain.