•pitchers

Text written by Albert Kilchesty

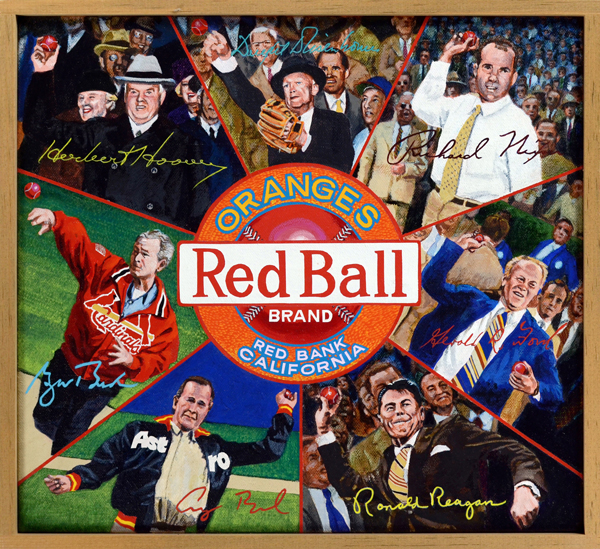

Red Ball Brand (private collection)

Looking over the roster of Republican presidents depicted here, one gets the sense that they would clobber their Democratic Party counterparts in a game of baseball. Clockwise from top left are Herbert Hoover, Dwight D. Eisenhower, Richard M. Nixon, Gerald Ford, Ronald Reagan, George H.W. Bush and his son George W. In addition to opening day duties, Hoover threw out first pitches in the 1930 and 1931 World Series; in Philadelphia prior to the start of the 1930 classic, fans greeted him with chants of “We want beer!” in reaction to its absence at the ballpark during Prohibition. Nixon was considered for the post of Commissioner of Baseball after his impeachment. Ford, despite his portrayal as an oaf, was a football star at the University of Michigan. Reagan’s athletic skills were suspect, but he did play both gridiron and diamond greats in films, once starring as the great pitcher Grover Cleveland Alexander (who was named for a president). In The Winning Team. George Bush père anchored first base for the Yale baseball team, picking up the nickname “Spikes.” Mementoes from his college career are on display at the Hall of Fame. Bush fils was part-owner of the Texas Rangers prior to his election; the Oliver Stone film W. famously concludes with an image of the president waiting to catch a fly ball that never descends into his glove.

First Pitch Brand

In the long history of ceremonial first pitches delivered by sitting (or standing) U.S. presidents, none have looked fitter on the mound than Barack Obama. The former senator from Illinois makes no bones about his love for the Chicago White Sox, the South Side’s representative in Major League Baseball since the dawn of the American League in 1901. Unlike the cuddly Cubs, their North Side neighbors, the Pale Hose don’t play in a bijoux park with ivy-covered walls and don’t draw much attention from the media. White Sox fans are working-class tough, hard-bitten and serious about their baseball. They also tend to be black, not white, reflecting the makeup of the surrounding community. The two teams do have one thing in common: they have repeatedly failed in the postseason. So when the White Sox demolished the Astros to win the 2005 World Series, breaking an 88-year pennant drought, the South Side exploded with joy. None seemed happier than President Obama, who was seen afterward sporting White Sox garb, and pleased to demonstrate his pitching form when asked.

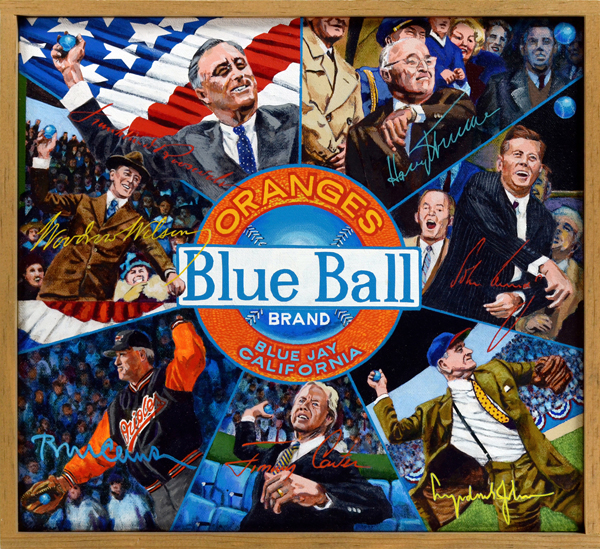

Blue Ball Brand (private collection)

For decades, the lowly Washington Senators kicked off the American League season by having the current president throw out the ceremonial first pitch. This tradition began in 1910, when the rotund William Howard Taft, who loved the game, inaugurated the season by lobbing a ball to Walter Johnson, the Senators’ starting pitcher. Since then, most U.S. presidents have participated in the event. This painting features seven presidents affiliated with the Democratic Party. Clockwise from top left are Franklin D. Roosevelt, Harry S Truman, John F. Kennedy, Lyndon B. Johnson, Jimmy Carter, Bill Clinton and Woodrow Wilson. Of this group only Truman, Johnson and Wilson had ties to the game as former college players. Jimmy Carter never threw out an official opening day pitch—his brother Billy subbed for him—but he did toss a few to start the season for the Atlanta Braves.

Bluegrass Senator Brand

One may be forgiven if this image creates a yen for fried chicken. That’s not the pitchman of KFC fame at top left but his prototype, the Kentucky Colonel, an honorifically bestowed title formerly given to any white man of means in the Bluegrass State. The pitch man falling off the mound during his follow-through is Hall of Famer Jim Bunning, author of no-hitters with the Detroit Tigers (1958) and Philadelphia Phillies (1964), the latter a perfect game. He is the first of five men to throw no-hitters in each league. Bunning entered politics after his baseball career ended, ultimately gaining office as the junior US Senator (R) from his home state of Kentucky (1998‒2010). A staunch conservative, his time in government was marred by odd behavior and a skein of offensive remarks. In 2006, Time magazine called him “The Underperformer” and named him one of America’s Five Worst Senators, saying he “shows little interest in policy unless it involves baseball.”

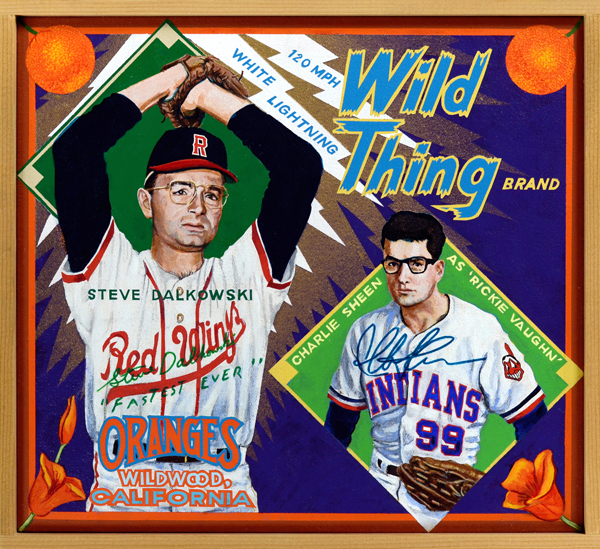

Wild Thing Brand

Those who saw Steve Dalkowski pitch as a Baltimore Orioles farmhand claim he was the fastest pitcher ever. Unfortunately for Steve, he was wilder than a wildebeest, routinely frightening anyone within the vicinity of home plate with uncontrollable 100 mph+ fastballs. Dalkowski (b. 1939), a violent and unmanageable alcoholic, nearly drank himself to death on several occasions. Despite many attempts to curb his wildness, nothing worked: no pitcher in the history of professional baseball struck out more men and walked more batters per nine-inning game than “White Lightning” Dalkowski. His legend spawned several fictional characters, including Nuke LaLoosh from the 1988 film Bull Durham, directed by former Orioles minor leaguer Ron Shelton, and Rickey Vaughn, erratic flamethrower in the film Major League. Vaughn’s mound appearances were introduced by the song “Wild Thing,” a 1966 recording by The Troggs. (In a curious twist, Charlie Sheen, who played Vaughn in the film, later became notorious as a wild child in his own right.) Although not depicted here, another “Wild Thing,” relief pitcher Mitch Williams, earned the nickname honestly by routinely walking the bases full before then striking out the side. His legend died ingloriously after he gave up a walk-off home run to Blue Jays outfielder Joe Carter in the sixth, and final, game of the 1993 World Series of hard work could help the pitcher in one respect: his lifetime batting average of .085 is among the worst ever for a pitcher.

Speedball Brand

A trio of pitchers, from left to right: Dwight Gooden, Denny McLain and Steve Howe. All three threw hard, all achieved stardom, all were undone by drugs and other problems. (The word “speedball” in this case refers not only to velocity, but also a mixture of cocaine and heroin delivered intravenously.) Gooden (b. 1964), nicknamed “Doctor K” or just “Doc,” had a brilliant rookie campaign with the Mets in 1984, winning Rookie of the Year honors with a record of 17‒9 and 276 strikeouts (k’s). After copping the Cy Young Award the following year, Gooden helped the Mets reach the 1986 postseason, crowned by a memorable World Series victory over the Boston Red Sox. Doc’s career then went into freefall, abetted by cocaine abuse. Denny McLain (b.1944) is the last player to win 30 or more games in a season; his 31 victories in 1968 shot the Detroit Tigers to World Series glory, and secured for the pitcher Cy Young and MVP honors. He, too, saw his career undermined by drugs, but in McLain’s case a high-flying lifestyle beset by multiple legal difficulties contributed to his downfall. Steve Howe (1958‒2006) was a relief ace for the Dodgers in the 1980s, but continued substance abuse resulted in multiple suspensions, destroying a career that once seemed so promising.

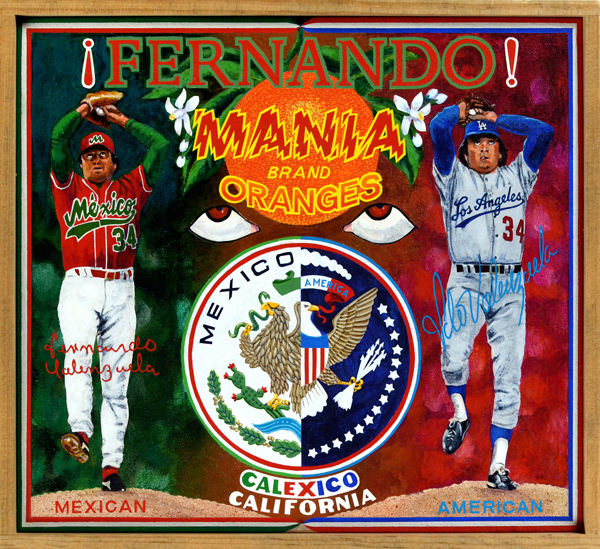

¡Fernando! Mania Brand (Baseball Reliquary collection)

In most baseball cities during the strike-shortened season of 1981, fans had little to cheer. They felt betrayed, abandoned and angry. In Los Angeles, though, fans felt mostly impatient: the strike had robbed them of the chance to watch a pitcher continue his assault on the record books. Early that season, the Dodgers had revealed their latest find, a young, chubby Mexican southpaw with a deadly screwball named Fernando Valenzuela. In short order Valenzuela (b. 1960) reeled off a skein of consecutive victories and shutouts, pitching as though invincible. The resulting escalation of excitement grew into a full-blown cultural phenomenon—Fernandomania—that would eventually sweep the country. Whenever he pitched at home, the atmosphere at Dodger Stadium would become transformed by an influx of flag waving, noisy, delirious Mexican fans, all come to celebrate their national hero. His appearances on the road generated similar enthusiasm. In Mexico an entire country came to a halt when Fernando pitched. He earned both the Cy Young and Rookie of the Year Awards in the National League for 1981, and continued to pitch well for the Dodgers into the early ’90s. He returned briefly to Mexico, leading Mazatlan to the Caribbean World Series, before closing out his Major League career in 1997. Although numerous Mexican players have starred in the Majors, none have succeeded as wildly as Valenzuela.

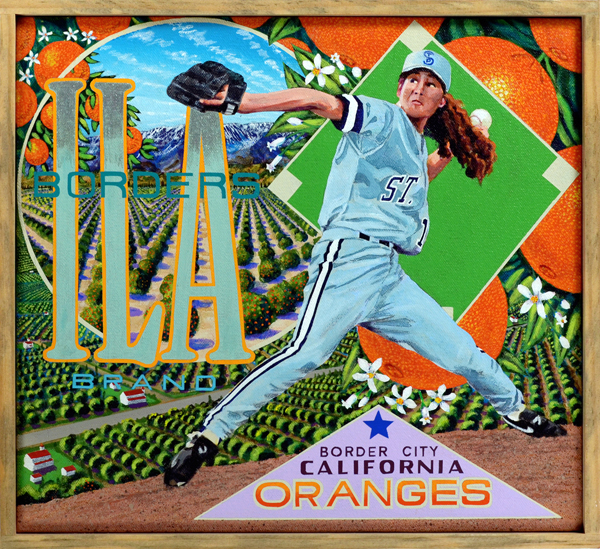

Ila Borders Brand

Ila Borders (b. 1975) is the second woman to start a men’s college baseball game and among the first female pitchers in integrated men’s professional baseball. The left-handed control specialist pitched in NAIA competition for Southern California College and Whittier College between 1994 and 1997. Later that year, Borders signed with the St. Paul Saints of the independent Northern League. Traded to the Duluth Dukes, on July 7, 1998 she became the first female pitcher to start a professional men’s game. She lost that game, but three weeks later became the first woman pitcher to win a pro game, besting the Sioux Falls Canaries 3‒1. Frustrated by injuries and illness, she moved to the Western League for the 2000 season. When she realized that her hopes to attract attention from a Major League affiliate were doomed, she retired midway through the season. In 2003 she was elected to the Baseball Reliquary’s Shrine of the Eternals for her pioneering efforts to end gender discrimination in the game.

Big Bird Brand

Mark Fidrych (1954‒2009) set the baseball world on fire in 1976 as a rookie pitcher for the Detroit Tigers. The tall right-hander with the mop of curly blond hair was nicknamed “Big Bird” or “The Bird” in reference to the Sesame Street character he resembled. Fidrych’s eccentric behavior—he would sometimes “talk” to the ball before throwing it—and lights-out pitching skill made him an instant folk hero around The Motor City and, shortly afterward, with baseball fans nationwide. He posted an All-Star rookie campaign, winning 19 games against 9 losses with a low 2.34 ERA, and was named AL Rookie of the Year for 1976. But few rookies, no matter how talented, can withstand the rigors of pitching 250 innings as a 21-year-old without showing signs of distress. Detroit’s valuable gate attraction succumbed to injury the following season, and never recovered the form of his rookie campaign. Nevertheless, the Big Bird achieved cult status, and is fondly remembered today for his one shining season as a star.

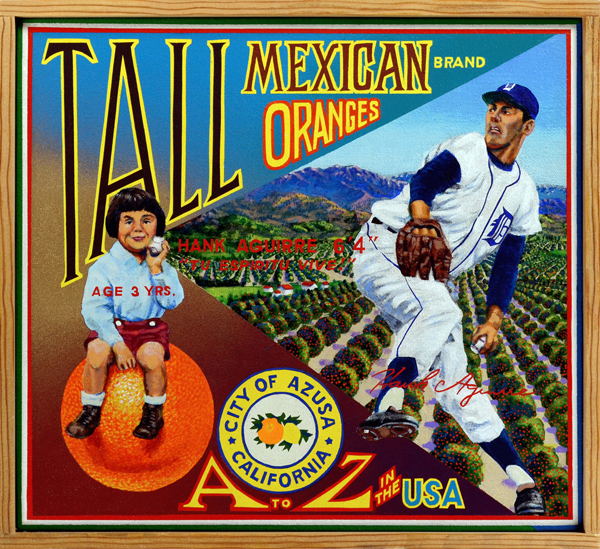

Tall Mexican Brand

Hank Aguirre, the Pride of Azusa, was a 6’ 4” left-handed pitcher who played with several teams during a sixteen-year career, notably the Detroit Tigers in the 1950s and ’60s. Aguirre’s father and mother relocated to the United States during the Mexican Revolution, settling outside Los Angeles where they opened a business, the Aguirre Tortillas Factory. Hank (1931‒1994) was signed by the Cleveland Indians and appeared in his first game during the 1956 season. He was groomed as a relief pitcher, and was used in that role almost exclusively until 1962, when injuries to Detroit’s pitching staff forced Hank into a starter’s role. He responded brilliantly with an All-Star season, posting 16 victories and leading the Major Leagues with a tiny 2.21 ERA. Upon retirement, Aguirre founded Mexican Industries, Inc., a Detroit-based company that provided specialized car parts to the automobile industry. Emphasizing minority hiring and community involvement, the company grew into a multi-million dollar enterprise. In 1987 Aguirre was named “Business Man of the Year” by the U.S. Hispanic Chamber of Commerce. Success through hard work is the theme of Aguirre’s life, but no amount of hard work could help the pitcher in one respect: his lifetime batting average of .085 is among the worst ever for a pitcher.

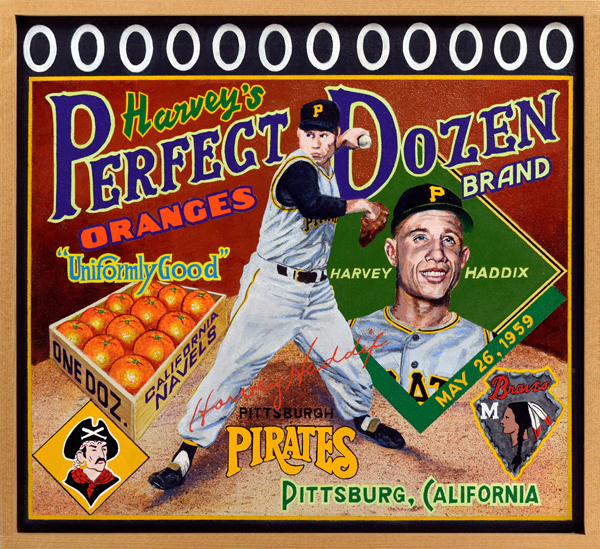

Harvey's Perfect Dozen Brand

Pirates southpaw Harvey Haddix—“The Kitten”—pitched the greatest game in baseball history, a perfect 12-inning outing undone by an error in the top of the thirteenth. Haddix (1925‒1994) had been a dependable starter for three teams before being acquired by the Pirates in 1959. In a game against the Milwaukee Braves on the evening of May 29, 1959, Haddix retired 36 consecutive Braves hitters without allowing a baserunner until Pirate third baseman Don Hoak committed a throwing error in the top of the 13th, allowing the leadoff batter to reach first. After Henry Aaron also reached base, Joe Adcock belted a home run to give the Braves and ostensible 3‒0 lead. However, due to a base running gaffe in which Adcock passed Aaron on the base paths, two runs were voided, making the final score 1‒0 in favor of Milwaukee. Haddix’s mound opponent, Warren Spahn, pitched a brilliant game as well, holding off the Pirates to notch the complete game, shutout victory.

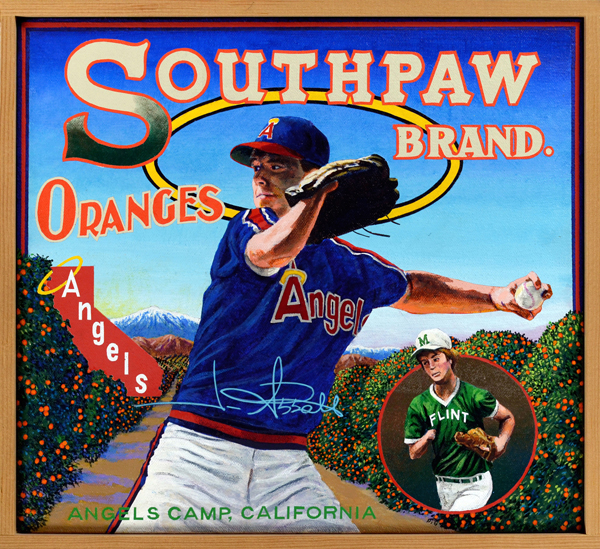

Southpaw Brand (Baseball Reliquary collection)

Jim Abbott was born without a right hand, but was blessed with such an abundance of natural athletic skill that he would reach the highest level of his sport without spending a single day in the minors. Abbott (b.1967) caught and threw a baseball with his good, left hand, a method he perfected as a Little Leaguer in his hometown of Flint, Michigan. Before delivering a pitch, Abbott would rest his glove on the end of his right forearm. After delivering the ball, he would swiftly slip his hand into the mitt, placing him in a position to field any ball hit toward him. He attended the University of Michigan, where he paced the Wolverines to two Big Ten championships. In 1987, Jim was named the recipient of the James E. Sullivan Award, an annual honor presented to the nation’s best amateur athlete. He was the first baseball player to win the award. The California Angeles selected him in the first round of the 1988 draft, and promoted him to the big club after he wowed the coaching staff during spring training. He debuted at home in April 1989 before a packed crowd buzzing with excitement. Although tagged with the loss, he turned in a respectable rookie season, finishing with a 12‒12 record with a 3.92 ERA. While pitching for the Yankees, Abbott pitched a no-hitter in September 1993. He struggled afterward, and retired in 1999. He is now a highly effective motivational speaker.