•the umpire

Text written by Albert Kilchesty

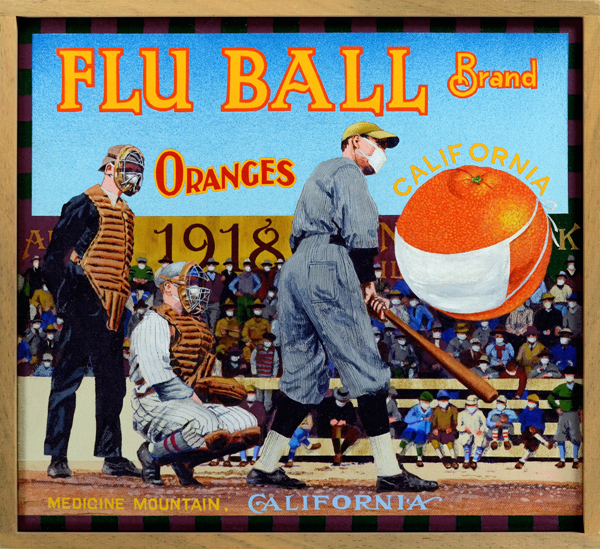

Flu Ball Brand (private collection)

The Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918 resulted in the deaths of an estimated 50 to 100 million people worldwide, one of the worst natural catastrophes in human history. From the world’s great cities to its most remote islands, none was spared. Young and old, the healthy and the frail, all succumbed to the virus. In the United States more than a half million deaths were linked to the illness, with Native American communities particularly hard hit. Wherever large crowds of people gathered—college football games, baseball games—public officials fretted. In some cases this fear led to the postponement of numerous sporting events. When teams did decide to play, a popular ditty of the time encouraged them to take precautions—“Obey the laws and wear the gauze. Protect your jaws from septic paws.” During one minor league game, players on both sides wore protective masks, as seen in this painting. With the Ebola virus and other strains threatening communities worldwide, it may not be long until we see similar measures adopted today.

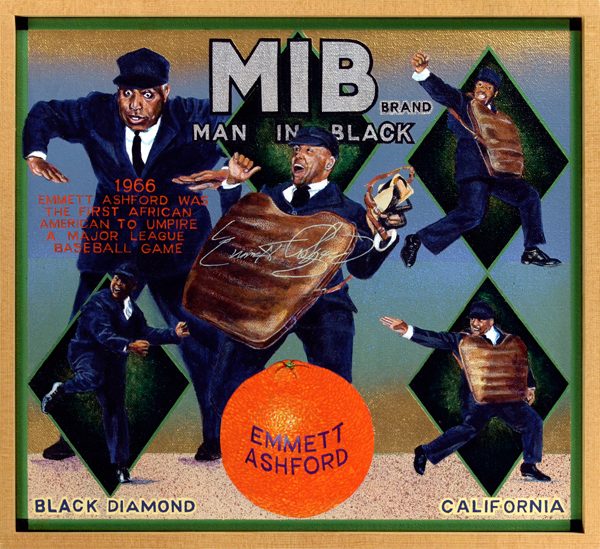

MIB Brand

Emmet Ashford was, as the painting indicates, the first African-American man in black to umpire in Major League Baseball. Ashford (1914‒1980), a seasoned minor league umpire, didn’t reach the majors until his early fifties, but when he debuted in the American League in 1966 he became an overnight sensation. “Ash” brought energy and style—two traits not normally associated with arbiters—to the game. The nattily dressed umpire delighted fans with an assortment of theatrical gestures and movements. Even The Sporting News, a bastion of conservatism, was moved to write, “For the first time in the history of the grand old American game, baseball fans may buy a ticket to watch an umpire perform.” His umpiring career was too brief, alas. He reached the mandatory retirement age of 55 in late 1969, and finished his career at the end of the following season. In 1971, the magnanimous Ashford was hired as public relations adviser by commissioner Bowie Kuhn. The umpire also appeared frequently on television and in films until his death from a heart attack at age 65. After cremation his ashes were interred in Cooperstown, home to the Hall of Fame.

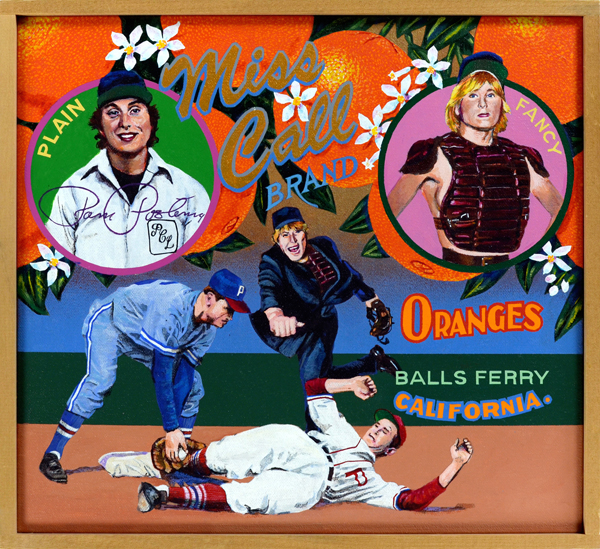

Miss Call Brand (Baseball Reliquary collection)

Baseball’s race problems have long been the subject of scrutiny, but the game’s gender problems have not. Women of all races and ethnic backgrounds have been denied positions within the game, and have yet to take a seat at the table that they more than likely set. The case of umpire Pam Postema illustrates this issue. Postema (b. 1954) came closer to becoming the first female umpire in major league history than anyone before. She slogged through every level of Organized Baseball, enduring unimaginable taunts and slurs, to prove her mettle as an equal. She was everything one could want from an umpire, tough but fair, knowledgeable and decisive. She had balls, but not where they count. In 1988 she became the first female umpire to officiate major league spring training games. Later that year she was tapped by commissioner A. Bartlett Giamatti to umpire the annual Hall of Fame Game, a major league exhibition contest played at Cooperstown. It seemed like just a matter of time before she got the call to work in The Show. But after her benefactor Giamatti died suddenly in 1989, that call never arrived. Frustrated that she was never going to crack baseball’s glass ceiling, she retired. Her 1992 book, You Gotta Have Balls to Make It in This League, is a candid document of her life in baseball. In 2000, Postema became the first woman elected to the Baseball Reliquary’s Shrine of the Eternals.

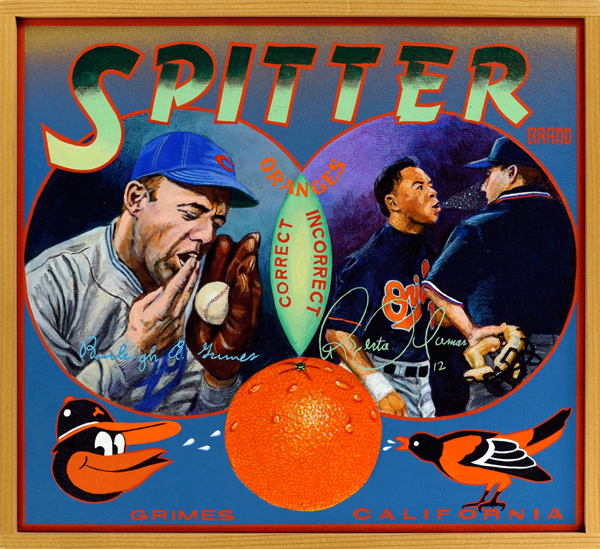

Spitter Brand (Baseball Reliquary collection)

Saliva and baseball have a long history together. All types of wet substances have been applied to baseballs in order to make them harder to hit. The spitball was the pitch of choice during the early twentieth century. Spitballs looked like fastballs to the batter, but the pitch would dip and dive at the last moment, making hitters look foolish. The spitball was outlawed in 1920, along with other doctored pitches like the shine ball and emery ball, but those pitchers who depended on the spitter for their livelihoods were allowed to continue throwing it. One of them, Burleigh Grimes, is seen here showing how he “loads up” a pitch. Any pitcher caught throwing a spitball today is ejected from the game, and often fined and suspended. Certain players have also been ejected for spitting on an umpire. In 1996, Roberto Alomar, then playing for the Orioles, spit on umpire John Hirschbeck during a heated argument. This act would damage Alomar’s otherwise sterling reputation, and would delay his entry to the Hall of Fame by a year. Many thought the voters had the incident in mind when Alomar failed to gain entry on the first ballot.