•labor / management

Text written by Albert Kilchesty

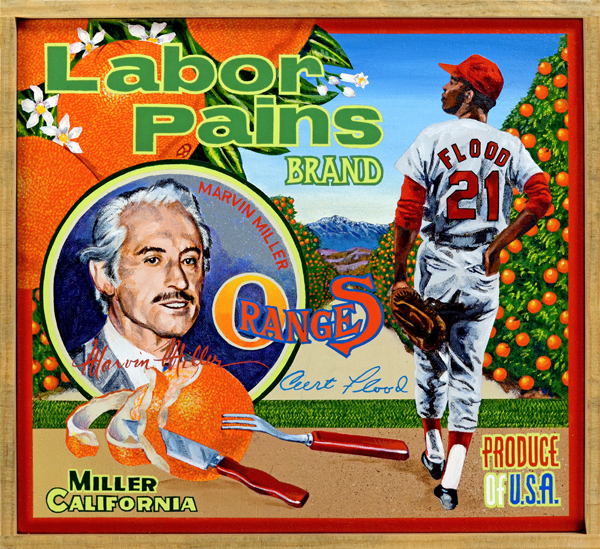

Labor Pains Brand (Baseball Reliquary collection)

Among the sacred tenets of free market capitalism is the right for a worker to sell his services to the highest bidder. Nothing prevents a worker from leaving one job to take another at a higher salary. In baseball, however, the standard player contract included an infamous article—the reserve clause—that bound a player to his team in perpetuity. A player could be sold, traded, placed on waivers or released at the whim of ownership. Although challenged periodically in the courts, the reserve clause held fast for a century, until St. Louis Cardinals All-Star outfielder Curt Flood decided to test its legality. Traded without his consent after the 1969 season, Flood (1938‒1997) refused to report to his new team, saying he no longer wished to be treated as a well-paid slave. His case climbed the judicial ladder all the way to the Supreme Court, which ruled in favor of ownership. Despite the ruling, Flood’s case represented the first serious blow against the reserve clause, which would finally be eliminated in the mid-seventies thanks in large part to Marvin Miller. A former union negotiator for the steel industry, Miller (1917‒2012) served as Executive Director of the Major League Baseball Players Association (MLBPA) from 1966 to 1982. Under his leadership the MLBPA was greatly strengthened, the reserve clause demolished; today it is among the most powerful labor unions in the country. The era of free agency ushered in under Miller’s supervision boosted player salaries significantly, leading to the astronomical salaries we see today.

Frau Ball

Of the handful of women to own baseball clubs, Marge Schott and Effa Manley were the most visible and, at times, the most controversial. Schott (1928‒2004) married into wealth and inherited her husband’s lucrative automobile dealerships upon his death. In 1984 she purchased a controlling interest in the Cincinnati Reds. She and her dog Schottsie, a lumbering St. Bernard who enjoyed defecating on the playing field, were the public face of the team for fifteen years. During her tenure, Schott repeatedly made racist remarks about African-Americans, Jews and the Japanese. She was banned by baseball for two years in 1996 after making absurd remarks about Adolf Hitler’s “enlightened” domestic policies. Schott relinquished her ownership shortly afterward. The burning question concerning Effa Manley (1897‒1981) concerned her race: “Was she white, or was she black?” With her husband Abe, king of the local numbers racket, Effa co-owned the Newark Eagles of the Negro National League from 1935 through 1946. Dynamic and creative, Effa played a central role in keeping Negro League baseball viable during difficult economic times. Throughout her life, Manley enjoyed the confusion that her light skin caused. She presented herself to the public as a white woman “passing” for black, a curious reversal of the norm, but no one other than Effa seemed to know the truth concerning her birth parents. Undeniably, she was a woman, a fact considerably more important than her racial makeup. The Baseball Hall of Fame recognized this by enshrining Effa in Cooperstown, the first woman to be accorded that honor.