•jewish american ballplayers

Text written by Albert Kilchesty

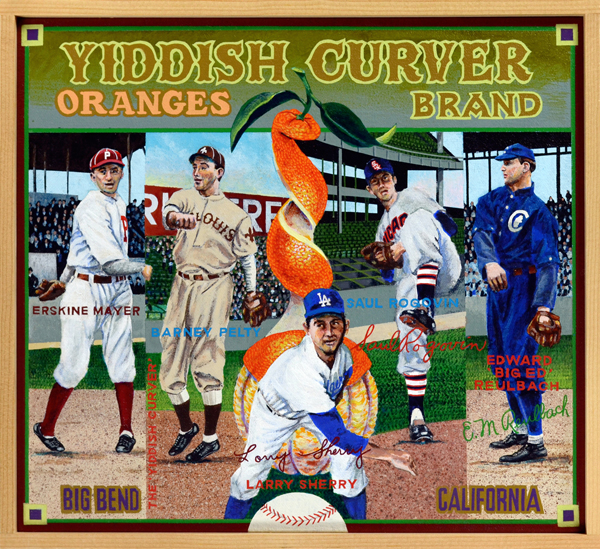

Yiddish Curver Brand

During baseball’s formative years, players of Jewish ancestry often played under anglicized versions of their surnames. This practice developed as a way to assimilate more easily into baseball culture, which was a haven for racists and the ignorant. By the turn of the twentieth century, Jewish players began to use their birth names, proudly and defiantly. Of the five curveball artists pictured here three played during the Deadball Era (1900‒1919): Erskine Mayer, Barney Pelty and Ed Reulbach. Mayer (1889‒1957) threw a nasty sidearm curve that made batters look foolish. A multiple 20-game winner, he was an important piece of the 1915 NL champion Phillies, and later pitched for the 1919 Black Sox. He is considered among the best Jewish pitchers in history, as is Barney Pelty (1880‒1939), the original “Jewish Curver.” Pelty’s career suffered as a result of playing for the perennially awful St. Louis Browns, but he was still able to post the best career ERA of any Jewish pitcher. Big Ed Reulbach (far right) was the workhorse of the Chicago Cubs pitching staff during their last extended period of glory. In 1908, Reulbach (1882‒1961) threw shutouts in both games of a doubleheader, the last man to notch complete games on the same day. That Cubs team was the last to win a World Series. Saul Rogovin and Larry Sherry baffled batters during the Fifties. Rogovin (1923‒1995) was a solid, if unspectacular, starter for four teams during his career. His yakker propelled him to the AL ERA title in 1951. Larry Sherry (foreground) was the savior of the Dodgers pitching staff in the team’s championship season of 1959. The Los Angeles native, whose older brother Norm was a big league catcher, served as the Dodgers top relief pitcher in the early 1960s.

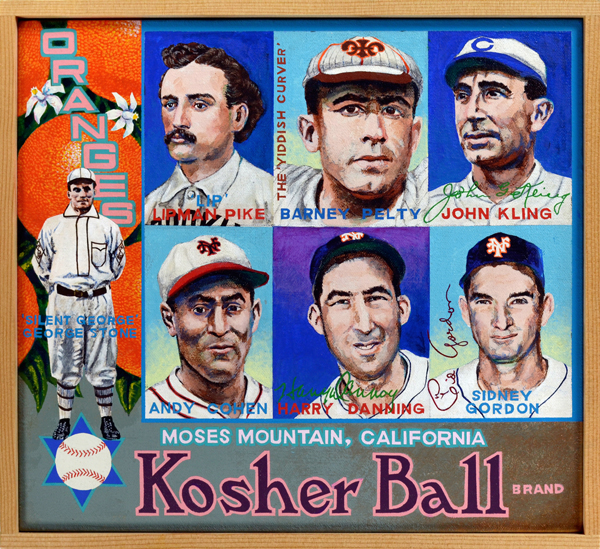

Kosher Ball Brand

The Star of David’s six points are represented by a cast of Jewish stars who point to the history of Jews in baseball. Standing on the left is the Moses of this piece, “Silent” George Stone, who left a career in banking at age 26 so he could play baseball. In 1906 he reached the Promised Land, winning the AL batting title as a player for the St. Louis Browns. Clockwise from top left: Lip Pike (1845‒1893), the first Jewish athlete to play professional baseball, known as “The Iron Batter,” played for numerous teams during the game’s nascence (1871 to 1887). Next is curveball artist Barney Pelty (see “The Yiddish Curver”) followed by Johnny Kling. Kling’s ethnic origin has been the subject of dispute—was he or wasn’t he Jewish?—but not his athletic talent. Catcher on the last Cubs team to win a World Series in 1908, Kling (1875‒1947) was also a champion pool player who exchanged a bat for a cue in mid-career. Brooklyn native Sid Gordon (1917‒1975) provided power for the Giants and Braves in the 1940s and ’50s. Babe Ruth called New York Giants durable receiver Harry “The Horse” Danning (1911‒2004) “the best catcher in baseball.” Harry picked up his nickname from the equine nature of his face, although it may also have referred to another physical quality. Infielder Andy Cohen (1904‒1988), “The Tuscaloosa Terror,” was signed by the NY Giants to attract more Jewish fans to games during the 1920s. Andy turned in two good seasons in 1928 and 1929, becoming so popular with fans that frozen concessions were renamed “ice cream Cohens” in his honor.

Beysbol Brand

This panoply of Jewish-American greats features at center a portrait of Barney Dreyfuss (1865‒1932), Major League executive and owner of the National League’s Pittsburgh Pirates franchise from 1900 until his death. Dreyfuss’s many contributions to the game include the building of Forbes Field, one the game’s earliest concrete and steel ballparks, and the creation of the modern World Series in 1903. He also played a central role in the banning of the spitball and other trick pitches in 1920. At top left is pitcher Ken Holtzman (b.1945), who didn’t require a bag of dirty tricks to win; he is the only twirler since the 1880s to throw two no-hitters for the Chicago Cubs, and would later pace the Oakland A’s to three consecutive World Series titles in the early ’70s. Beside him is slugging third sacker Al “Flip” Rosen (1924‒2015), unanimous American League MVP in 1953, who spent the entirety of his playing career with the Cleveland Indians, and would later become a respected executive with the Yankees, Astros and Giants. Next is the incomparable Sandy Koufax (b.1935), the most dominant pitcher of his day—a three-time Cy Young Award winner, perennial strikeout king and author of four no-hit games, one of them a perfecto in 1965. Koufax was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1972, joining there the first Jewish superstar of team sport, Hank Greenberg (1911‒1986), who entered the Hall in 1956. Supplanting Jimmie Foxx as the most lethal right-handed hitter in the AL, the “Hebrew Hammer” smashed 58 home runs for the Detroit Tigers in 1935 and drove in an incredible 183 runs in 1937, the AL record for a right-handed batter. While a young player, he endured every anti-Semitic slur imaginable and would later become an outspoken advocate for ethnic and racial equality. Greenberg was a hero to Jewish kids, who drove their elder’s nuts with their passion for this crazy American game: “You mean these men get paid to play?” Thanks to Greenberg they, too, would soon learn to love beysbol.