•japanese & chinese in america

Text written by Albert Kilchesty

Issei Ball Brand

The first wave of Japanese immigrants—Issei—organized baseball teams in the early twentieth century as a way of building cultural connections to European Americans. Many had already developed a love for the game in Japan and used baseball as a means for rapid assimilation into American culture, just as other immigrants groups would do. However, discrimination and continued exclusion from the mainstream forced Japanese Americans to develop their own baseball institutions. This painting celebrates the first Issei nine in California, the Fuji club, organized in 1903. The team was founded by an artist (fitting in this case), Chiura Obata. In short order, Issei teams would flourish across the west, in Washington, Colorado, Wyoming and, of course, California.

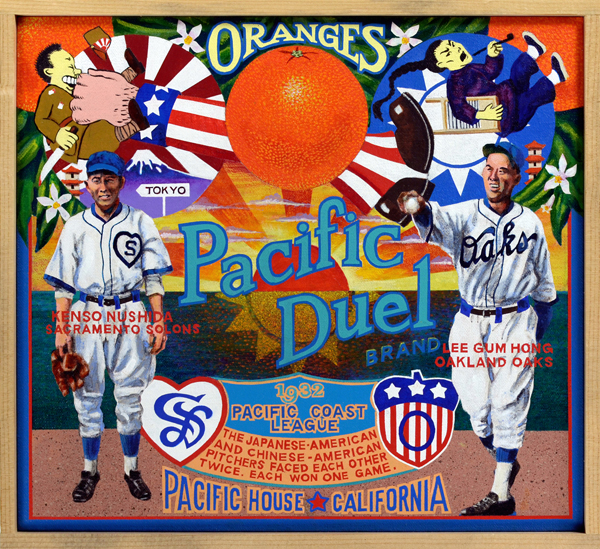

Pacific Duel Brand

During the depths of the Depression, the two worst teams in the Pacific Coast League (PCL), the Oakland Oaks and Sacramento Solons (or Senators), were taking a beating at the gate. In a desperate attempt to boost attendance, the Solons signed a pitcher from the California Nisei leagues, tiny Kenso Nushida, as an appeal to the region’s Japanese-American community. Meanwhile in Oakland, the Oaks signed a Chinese-American pitcher, the hulking Lee Gum Hong (who had played under the name Al Bowen), in an attempt to attract fans to their games. Each proved a success with their respective clubs, so it was only a matter of time until both franchise owners decided to pit one against the other in what would be billed as the Sino-Japanese War Battle Royale of the Pacific Coast League. Amid much ballyhoo and excitement, the two squared off in a pair of games during the 1932 season. Each received a no-decision in the first game as both exited early. In the follow-up, Nushida left for an early shower as Hong hung on for a 7‒6 win. The great duel was never repeated, and it really wasn’t much of a duel at that. Still, the Chinese can claim the edge in this national battle for baseball supremacy.

Chinese Brand

Uses of the word Chinese and its derivatives in a baseball context are exclusively derogatory. For example, a “Chinese Home Run” or “Dink Shot” refers to a ball hit down the foul line that just barely clears the fence—a cheap tater, the type often lofted in the old Polo Grounds or down by Pesky’s Pole in Fenway Park. Slurs of this sort have been endemic throughout baseball history. So it may surprise many to learn that the barnstorming Hawaiian Travelers, a team composed mostly of ethnic Chinese from the islands, played a series of well-publicized exhibitions throughout the mainland early in the twentieth century. The “Traveling All-Chinese” team depicted here, a group of students from the University of Hawaii, posted a record of 80 wins against 54 losses in games played during 1914. The star of the club was pitcher Apau Kau, who the Philadelphia Public Record called “one of the sensations of baseball this season . . . without question the greatest hurler of his nationality.” The Indianapolis Star added, in language all too common at the time, “These Mongolian youngsters have taken to the American game as though it had been theirs for long generations, only they have orientalized it . . .” Posterity hasn’t recorded exactly what that means, but the team did powder plenty of home runs—legitimate blasts—as their sterling won-loss record attests.