•gambling on baseball

Text written by Albert Kilchesty

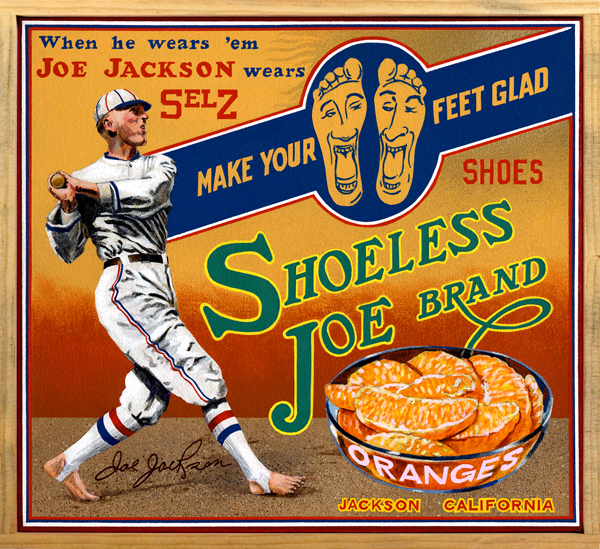

Shoeless Joe Brand (private collection)

Outfielder “Shoeless” Joe Jackson is considered among the best natural hitters in baseball history. Even the obstreperous Ty Cobb, never known to laud the ability of others, claimed that Jackson had the sweetest swing he ever saw. Jackson (1889‒1951) was an illiterate mill hand from South Carolina who starred for his company’s baseball team before signing a deal with Connie Mack’s Philadelphia Athletics in 1908. He received his nickname because he reportedly played a game in his stocking feet because his new shoes didn’t fit properly. His early career was marred by insecurities generated by his lack of education and a type of mental cruelty experienced by many young Southern men who toiled in the great cities of the North at that time. He finally grew comfortable after being traded to Cleveland in 1911, a season in which he batted .408. Traded to the White Sox in the middle of the 1915 season, Joe led his new team to the world championship title in 1917 and the AL pennant in 1919. He was one of eight “Black Sox” banned from baseball for life after his role as a co-conspirator in the fixing of the 1919 World Series came to light. Some contend that Jackson was innocent, bullied into the conspiracy by his teammates. Others point to Joe’s acceptance of a $5000 bribe to “lay down” as an indication of his guilt. Whatever one’s opinion, it remains clear that Shoeless Joe was a tragic figure, a man whose human limitations contributed to his downfall. By the way, this painting is a near-exact replication of an advertisement from the ‘teens.

Black Sox Brand (private collection)

Without gambling and gamblers professional sport as we know it today wouldn’t exist. That’s a fact. Huge sums were routinely won, and lost, by betting on the outcome of early bare-knuckled prize fights, horse races, foot races, dog and cock fights—any activity that had a yes/no, win/lose, this/that outcome lured bettors in droves. And wherever huge sums were at stake, there were those who attempted to cash in by “fixing” the results. Gambling affected baseball almost immediately upon the game’s growth as a professional or semi-professional enterprise. The earliest known fixed game took place in 1865 between the New York Mutuals and Brooklyn Eckfords; three Mutuals players admitted to throwing the game by committing a series of obvious errors during a Brooklyn 11-run inning. A sign posted outside a ballpark told customers in the late-nineteenth century all they needed to know: “No Game Played Between These Two Teams Is To Be Trusted.” As the century turned, betting at ballparks was endemic. Despite this, traditional histories of baseball point to the fixing of the 1919 World Series as an anomaly. It wasn’t. Eight Chicago players, some more culpable than others, conspired with gamblers bankrolled by the evil genius Arnold Rothstein to throw the series in favor of the inferior Cincinnati Reds. These “Black Sox” were exonerated by the Chicago courts, but were subsequently banned from further play by Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis, newly installed in that position by owners who feared that the public would not support an activity perceived as “unclean.” That some of these same owners may have enjoyed betting on games was conveniently forgotten.

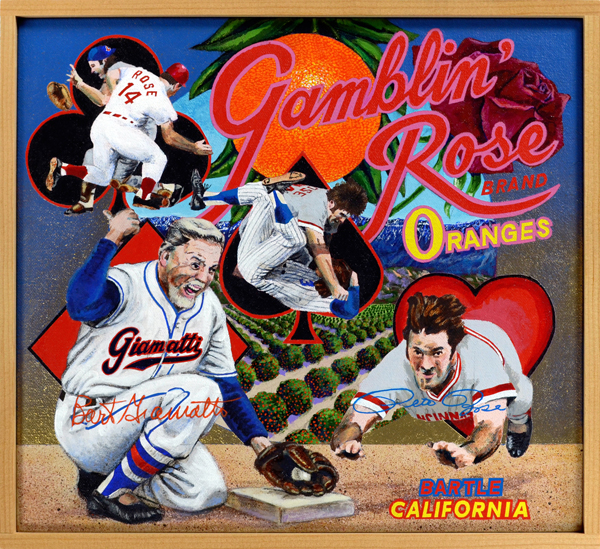

Gamblin' Rose Brand

Self-proclaimed “Hit King” Pete Rose (b. 1941) was at the center of the worst gambling scandal in baseball since the 1919 Black Sox. The Cincinnati native lived out his dream of playing for his hometown club, the Reds, and served as the spark which ignited the Big Red Machine juggernaut during the 1970s. He would fill the same role with the Phillies, leading them to their first World Series victory in 1980. In a career that spanned the years 1963 through 1986, Rose amassed a total of 4,256 hits, an all-time record. He was known throughout the game as a heavy bettor on other sports, but repeatedly insisted that he never bet on baseball. In 1989 Rose, now the manager of the Reds, was banned from baseball for life by A. Bartlett Giamatti, Commissioner of Baseball, after a thorough investigation revealed that Rose did indeed bet on baseball games, including those played by his own team. Rose denied the charges, of course, but the evidence proved otherwise. Giamatti did say, however, that Rose could periodically appeal for re-instatement, but his efforts thus far have proved futile. Rose was also banned from election to the Hall of Fame, but this didn’t prevent the Reds from announcing that Rose would be enshrined in the Cincinnati Reds Hall of Fame in 2016. Giamatti, father of the actor Paul Giamatti, died shortly after the Rose ruling. It’s been suggested that the strain imposed by the Rose case was a contributing factor to his fatal heart attack.